Who Killed J.S. Bach

Reviewed by Steven G. Kellman

During the final months of his life, Johann Sebastian Bach, who died in 1750, became blind. The composer underwent eye surgery, twice, without anesthesia, at the hands of “Chevalier” John Taylor, a self-aggrandizing charlatan who is believed to have blinded hundreds of hapless patients. The procedure is thought to have killed Bach.

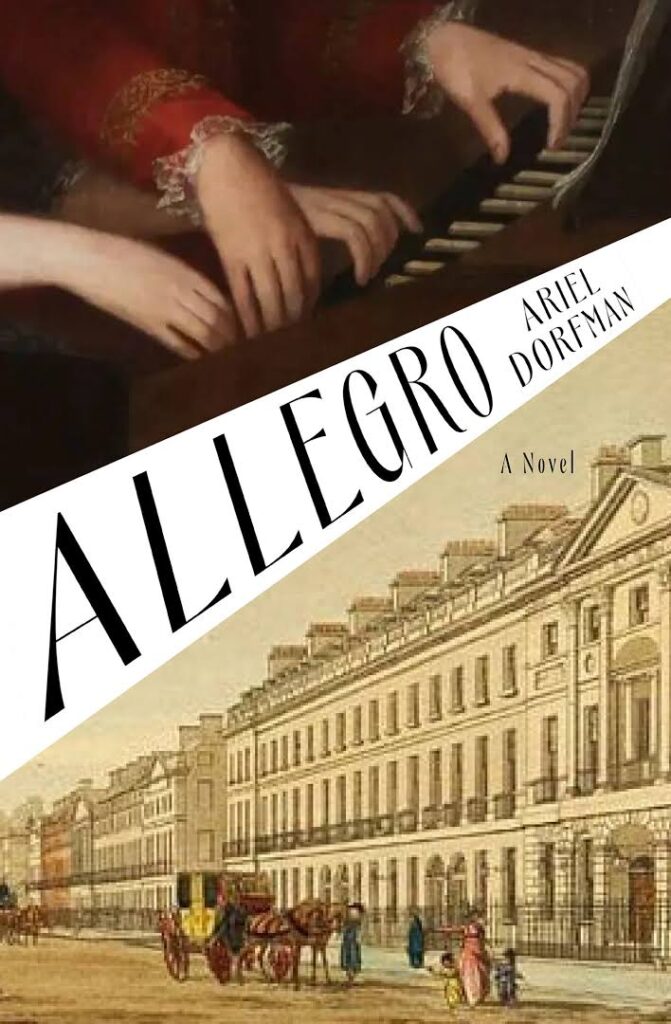

The premise of Ariel Dorfman’s Allegro is that it might not have been that simple. At the heart of his previous novel, The Suicide Museum, Dorfman, who has written often about surviving the violent Pinochet coup in Chile, is another secret – the truth behind the official account that Salvador Allende, the deposed president, died by his own hand. The question haunting the new novel is: Did botched ophthalmic surgery really kill Bach?

Narrated by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, who was born six years after Bach’s death, Allegro begins in London in 1765. Following the performance of his first symphony, Mozart, a nine-year-old prodigy, is cornered by a shadowy figure who identifies himself as Jack Taylor, son of the surgeon who treated Bach. Taylor entreats the young musician to intercede with his mentor, Johann Christian “Christel” Bach, the youngest son of Johann Sebastian. He asks Mozart to set up a meeting with Christel, who has refused to have anything to do with him, in order to convince him that his father, John Taylor, has been defamed. The younger Taylor wants to present Christel with information that would absolve his vilified father of any culpability for the death of the elder Bach.

Christel refuses to have anything to do with Taylor, but, during subsequent chapters set in later years in Paris, Taylor persists in trying to convince Mozart and then Christel that his father has been maligned. He tells of a lost letter sent to George Frideric Handel that would exonerate the elder Taylor. An exact contemporary of Johann Sebastian Bach, Handel, too, died blind following surgery by John Taylor.

It requires a generous suspension of disbelief to accept the fact that Mozart, who spoke German, Italian, and French but not English, is telling this story in 21st-century English. Nor would he be capable of narrating the novel in Spanish, although the first version of Allegro was published in Spanish in Barcelona in 2015. Perfectly bilingual, Dorfman is privileged to translate himself between Spanish and English. After writing his 1998 memoir Heading South, Looking North in English, he reimagined it in Spanish a few months later as Rumbo al Sur, deseando el Norte, altering North American idioms and cultural references to target readers in South America. An autotranslator can take liberties that a hired translator would not dare. I have not seen the Spanish version of Allegro, but since neither North nor South America figures in the story, it is unlikely that the Spanish and English texts differ significantly.

Allegro takes its title from the Italian musical instruction for brisk, lively performance and its style from the vivacious personality of Mozart, who, the reader knows, will be dead at 35. The premature loss of those he loves challenges him and deepens his music. Overwhelmed by the death of his beloved Maman, Mozart asks himself: “Why am I here?” His response explains the magnificent plenitude of Mozart’s contributions to the repertoire of symphonic, operatic, chamber, and choral creations: “I was here to prove God’s goodness simply by sitting at a clavier and letting the air welcome the sounds, let the universe breathe me into existence as my imagination overflowed like a fountain, like a flood, like a lake and a sea and an ocean.”

Much later, Mozart visits the grave of Johann Sebastian Bach, his august predecessor, in Leipzig. Whether or not he accepts the preposterous story Jack Taylor told, the younger musician has learned to view art as defiance of death. He has come to believe that “. . . from the moment we are born we humans are always singing some sort of requiem for ourselves, and all the other souls, the only sin if that requiem were not to celebrate joy and life as we fade away.” Several composers have tried to complete the sublime Requiem Mass, which Mozart did not live to finish. In his own canny, sprightly way, Dorfman furnishes the final word.————————————————————————————————————–Allegro by Ariel Dorfman; Other Press; 2025; $17.99.

Steve,

What a good review of Ariel’s new book – almost a John Grissom meets The Fugative. Thanks for the words. Stay in touch.

jgc

George Cisneros