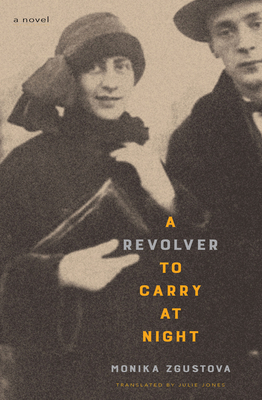

A Novel About Novelist Vladimir Nabokov

Reviewed By Steven G. Kellman

Vladimir Nabokov was not fond of biographers. He called them “psychoplagiarists” and even sued, unsuccessfully, to prevent one from publishing a book about him. There are now several biographies of Nabokov, including Brian Boyd’s two-volume cradle-to-grave account, in addition to Véra, Stacy Schiff’s Pulitzer Prize-winning study of the author’s wife. But biographers are handicapped by the obligation to record even the life’s dull stretches. Concentrating, instead, on a few dramatic moments, Monika Zgustova has crafted a short, intense nonfiction novel about Vladimir, Véra, and their son Dmitri.

It is no surprise that Zgustova, a Czech who lives in Barcelona and writes in Spanish, would be drawn to the translingual Nabokov, a verbal virtuoso in Russian, French, and English. He lived his life in three languages and six countries. Born into privilege in 1899 in St. Petersburg, he fled the Bolshevik Revolution and settled in Berlin, with a detour to Cambridge to study French literature. When the Nazis came to power, he and his Jewish wife, Véra Slonim, resettled in Paris. When the Germans invaded France, they decamped for America on the last available ship. Vladimir taught at Wellesley and Cornell, until the scandalous success of Lolita enabled the Nabokovs to retire to the Montreux Palace Hotel in Switzerland, where Vladimir died in 1977.

Véra, who died in 1991, dominates Zgustova’s book. It is she who carries a loaded Browning pistol in her purse and thwarts her husband’s “weakness for women” by monitoring his lectures and intercepting his love letters. Their son describes her as “a Mafia boss,” and it is she who insists that, to make his mark, Vladimir must switch to English. “Giving up his Russian, that was so flexible and so dear to him, and taking on a language when he was less than a hundred percent comfortable with its nuances,” writes Zgustova, “was one of the tragedies of his life.” When, despairing over publishers’ refusal to take a chance on Lolita, Vladimir attempts to burn the manuscript, Véra retrieves it from the flames. She is the one who types all his texts and drives their car. Although Vladimir learns to love America, she insists they move back to Europe.

In Zgustova’s reading, Véra yearns to do something great but acknowledges that she lacks creative genius. Unable to fulfill her grand ambitions on her own, “she decided to realize the work of her life by creating someone whom she could help by fusing with him and becoming part of his creation.” So she latches on to a promising young poet who is, like her, a Russian émigré and makes him her lifelong project. She curbs Vladimir’s capriciousness and defends their marriage against his digressions.

A Revolver to Carry at Night begins in 1977, during Vladimir’s waning days. He leaves behind 138 index cards, notes toward his final opus, The Original of Laura. Widow and son will struggle with whether to publish the fragment posthumously. Vladimir’s mind wanders backward. He thinks about Uncle Ruka, who sexually molested him but also made him heir to the richest fortune in Russia. He recalls the costume party in Berlin at which Véra, wearing the mask of a wolf, introduced herself.

The second section is anchored in 1937, when, following their affair in Paris, Irina Guadanini stalks Vladimir in Cannes. With both a wife and a lover, we are told, “He could not decide between the two of them and was unwilling to give up either one.” However, Véra issues an ultimatum: Give up Irina, or you will never see your wife and son again. Zgustova suggests that being obliged to renounce his heart’s desire inspired Nabokov’s brilliant story “Cloud, Castle, Lake.” She also sees Irina as the model for Liza Wind, the selfish, mercenary wife in Pnin, though she seems more akin to Mira Belochkin, Timofey Pnin’s lost love murdered at Buchenwald.

The next section is set in 1964, when Véra is in New York to see Dmitri, now an opera singer, perform at the Met (Vladimir has no taste for music, and his son chose a career that would not compete with his father’s). Vladimir will give a talk at Harvard the next day, and Véra insists on driving alone all night to join him in Massachusetts.

In the final section, it is 1990, and Véra is widowed and Dmitri disabled, after an automobile accident that ends his musical career. Véra is still in Switzerland, attempting to translate Pale Fire into Russian and understand the legacy of her complicated husband.

Vladimir Nabokov, who sought to deflect interest away from his person and toward his work, would likely be appalled at the “psychoplagiarism” that Zgustova’s book represents. Nevertheless, if fiction is disguised biography, nothing is important except the quality of the disguise. It is one thing to rubberneck the calamities that befall Julius Caesar and Richard III, figures insulated by the depths of history. It is quite another to make literature out of people who only recently walked the earth. It is somewhat creepy to gawk at the messy private lives of Vladimir and Véra Nabokov. In Monika Zgustova’s pointed prose, capably translated by Julie Jones, it is also fascinating.

————————————————————————————————————-

“A revolver to Carry at Night” by Monika Zgustova; translated by Julie Jones; New York Other Press

2024, $15.99

Great review, Professor Kellman. I was surprised you didn’t allude to his autobiography, Speak Memory: An Autobiography Revisited. It is dedicated to Vera.

What a concise and well-written review. I’ve already reserved the book at the library.