Book Review

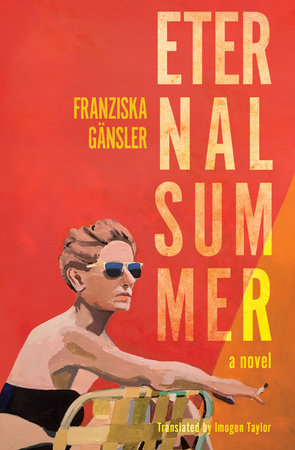

Eternal Summer by Franziska Gänsler

Reviewed by Steven G. Kellman

The grand spas of Europe provide elegant settings for wondrous human collisions in works by Anton Chekhov, Fyodor Dostoyevsky, Thomas Mann, and others. But Bad Heim, the German resort town in Franziska Gänsler’s sizzling debut novel is extraordinarily hot – in the sense not of trendy but scalding. Wildfires rage in the forest just across the river, and the noxious air is barely breathable. It is an environmental disaster zone. Only one hotel remains open in Bad Heim, and a taciturn woman and her very young daughter are its only guests.

Iris Lehmann, the narrator of Eternal Summer, is the proprietor of that hotel, and, while trying to maintain her daily, solitary routines despite the climate disaster, she is puzzled by her guests. Who are they? Why did they come to inhale the toxic fumes of Bad Heim during an indefinite stay? They keep to themselves and are unresponsive to Iris’s questions, but gradually she learns that the mother is named Dori and her daughter Ilya. A telephone call seems to provide further information. The caller, who identifies himself as a doctor named Alexander Vargas, asks whether Iris can help him locate his wife and child. He believes they left their home in Berlin and headed for Bad Heim.

Remembering how her own mother, who died at 32, was bullied by her grandfather, Iris is inclined to side with Dori against her husband. To his repeated calls, she responds that she has no knowledge of the woman and child he is looking for. Iris is attracted to Dori and fantasizes about building a life together. “It was years since I’d touched another body,’ she says. “Years since I felt anything.” Dori confides to Iris that her husband routinely belittled her and accused her of being unfit for motherhood. “A woman like you shouldn’t have a child,” he told her. In what might seem a kind of gaslighting, he tried to convince her that she was dangerously unstable.

On the other hand, evidence that Dori is indeed unstable keeps surfacing. She confesses to a moment of derangement in which, while holding Ilya, she jumped down a flight of stairs. She slips out of her hotel room at night and roams the smoldering region. She allows her young daughter to wander off on her own. Dori is a professional actress, and it is hard to tell which behavior of hers constitutes performance. By confining the story to Iris’s lonely and limited perspective, Gänsler maintains tension and an aching ambiguity. Is Iris helping or hurting Dori and Ilya by shielding them from Alexander? Is Iris, conscious of the poverty of her life, acting out of her own compulsions? “I had nothing to offer but a place that was barely habitable,” she says.

After a few days, the conflagration has become so overpowering that a group of idealists protesting environmental devastation packs up their encampment near the flames. Two militant young women, Cleo and Lou, take temporary refuge in Iris’s hotel. For them, the crisis is not just in the forest beside Bad Heim. “It was about the gender perspective, about consumerism, personal responsibility, sexuality, social structures,” they explain. That is also a fair summary of the themes pervading Eternal Summer. This is a dystopian novel of global warming set in a very near future not too distant from the blazes that have been consuming California, Australia, and Hawaii. However, the climate catastrophe is the book’s setting, not its purpose. It is a metaphor for the torrid feelings of the characters, and the fact that heat, smoke, and ashes are taken for granted makes the human drama all the more ominous.

A Rubenesque neighbor called Baby drops in, armed with tequila, and, amid the soot, sweat, and dust, Bad Heim briefly becomes a precarious society of woozy women. In the grimy darkness outside, trees surrender to the spreading blaze, and an anxious husband seeks his wife and child. “Thy eternal summer shall not fade,” Shakespeare assures his beloved in Sonnet 18. But the eternal summer promised in the title of Gänsler’s terse, intense novel is not a season for merriment; it is the inferno. She has constructed it out of short, singular sentences that, translated into English from the German by Imogen Taylor, resound like the phone ring each time Alexander calls.

—————————————————————————————————————-

Eternal Summer; by Franziska Gänsler; translated By Imogen Taylor; Other Press; 2025; $16.00.