Carlos Cortes’ Faux Bois Artistic Alchemy

By SUSAN YERKES, Contributing Writer

While taking a walk along San Antonio’s famous River Walk, you may be startled by a wild, rocky grotto on the Museum Reach of the promenade. It’s a magic place, with a trickling waterfall and a huge spirit face looming in the rock. Rest on a handsome wooden bench in the shade and wonder what quirk of nature carved the stone in this curious pattern.

Surprise! Nature’s only part in this grotto was inspiration. The grotto, the bench and two more benches across the river aren’t stone and wood. They’re beautifully sculpted out of cement – the creations of San Antonio’s artist, Carlos Cortés.

Cortés, 64, is the third-generation steward of a creative tradition — the art of trabajo rústico (rustic work), or faux bois (false wood). This artistic alchemy turns plain cement and metal into forms of nature so perfectly detailed that they are virtually indistinguishable from the real thing.

The mystical Grotto on the River Walk, the elaborate, patterned railings of the Witte’s H-E-B Treehouse, and a large, eye-catching palapa, at Landa Gardens in New Braunfels – are all examples of Cortés’ exacting work. So are countless benches, palapas and bridges, mission-shaped birdhouses, and vine-covered arbors found in both public and private places throughout the city and around the country. One of his most famous creations is the 2,100-pound faux bois table he made for the home of decorating diva Martha Stewart, who fell in love with the art when she saw his work.

While the designs and the process of creating trabajo rústico are precise and often complex, the tools of the trade are simple.

“You have the trowels, maybe a wheelbarrow, a shovel…you can buy cement in a bag and you use rebar,” Cortés said. “Then you sculpt a lot of it with your hands, you start with fingers and then a trowel and a chip brush.”

The armature of the pieces is fashioned from rebar, which is wrapped with layers of wire mesh to give it shape. Then three coats of cement are usually applied. The final coat is the one that bears the fine details that mimic nature. The finished piece is often stained with colors that complete the illusion of nature. Obviously, the sculptor’s skill is key, as is the mixture of the cement and the materials used to stain the piece. Over decades Cortés has become a master of all aspects of the art form. For some work with repetitive pieces, or specific forms, he creates cement or plaster-of-paris molds.

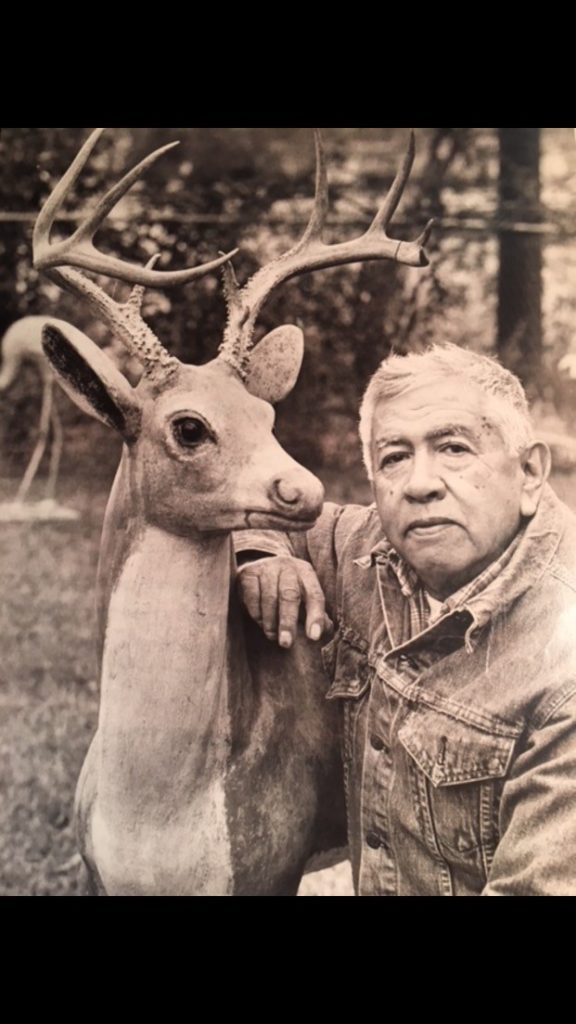

When we visited his premises, we noticed a blocky animal form standing in front of a corrugated metal building in the lot. He explained that he was busy restoring a mold of a life-sized doe his father, trabajo rústico artist Máximo Cortés made almost a century ago.

“Concrete is a really heavy material to make molds for casting. It’s a dying art,” Cortés said. “My dad was very talented,” he said. “His molds are very intricate. There are about 35 pieces in that mold. You have to make sure you don’t have an undercut your piece could get caught on when you’re pulling it out of the mold.”

Cortés learned the craft at an early age.

“I grew up with my dad doing it at home in his workshop, so it was right there –I could see it,” he said.

He didn’t plan to continue his father’s artistic legacy – in fact, he said, Máximo encouraged him to go to college and settle into a more traditional profession, like architecture or medicine. But after a career in drafting, a skill that has helped him with some of his larger works, he moved back to San Antonio in his 30s to work with his dad, who was by that time in his early eighties.

“When I realized this is what I was going to do I asked him a lot of questions. But he was a very humble person. He didn’t talk much,” Cortés said. “So, I learned just by being around him. You do it, and you follow what he’s doing and mimic it. I think anybody can learn what I do. You just need to practice it, practice it, practice it. I’ve been practicing now for a long time.”

Maximo Cortés kept working into his 90s, doing mostly private commissions that were much smaller than some of his son’s large public works.

“My dad was incredibly talented, but because he worked mostly on smaller individual commissions his work was on a smaller scale. Also, his work has been kind of overlooked because of my great- uncle Dionicio Rodriguez, who did a lot of large public pieces.”

Cortés and his father are two of the key figures featured in a new book, Artisans of Trabajo Rústico: the Legacy of Dionicio Rodriguez, by San Antonian Patsy Light, with hundreds of photographs by photographer Kent Rush. Light’s earlier book, Capturing Nature: The Cement Sculpture of Dionicio Rodriguez, is a thoroughly researched homage to Rodriguez, the late trabajo rústico artist who brought his craft from Mexico to San Antonio in 1924.

The towering Torii Gate at the Japanese Tea Gardens, a palapa-style trolley stop in Alamo Heights by Central Market, the rocky Stations of the Cross and small rustic grotto at St. Anthony de Padua Church, the Urrutia Gate now at the San Antonio Museum of Art, the pedestrian bridge and many other works in Brackenridge Park – all of these and many more pieces show Rodriguez’s craftsmanship.

Twenty-one of Rodriguez’s pieces in locations from Texas to Tennessee and Michigan, are listed in the National Historic Register, thanks to research by Light and conservationist Maria Watson Pfeiffer.

“We have the majority of them in San Antonio,” Light said with pride.

Light’s interest in Rodriguez led her to delve into the work of other trabajo rústico artists in the recent book, as well as the history of the craft.

“When I first learned about Dionicio Rodriguez and started finding his work, it was like opening a treasure chest,” she said. “Then it went on, and the treasure chest is still open.”

Some of the talented artisans who worked with Rodriguez on large-scale projects – including Máximo Cortés and now Carlos, carry on his legacy. It’s a family tradition. Rodriguez was Máximo Cortés’ uncle by marriage. Maximo’s father-in-law Julius Tobar also worked with Rodriguez, and Tobar’s grandson Jacob Tobar, an accomplished faux bois artist in his own right, often works with Carlos.

They have recently collaborated on restoring some of Rodriguez’s works that have been damaged by time or circumstance. A bench and palapa in Brackenridge Park, broken when a tree fell on them, took almost a year to restore because, while working on the structure, they found that at some point Rodriguez himself had reworked the piece. The original was encased in a kind of outer shell with substantial changes. They’re also restoring some pieces Rodriguez made for Miraflores, the elaborate garden of one of his first San Antonio patrons, which is now part of Brackenridge Park. Cortés’ youngest son, Cordero is also working with him these days. Cortés says he isn’t sure who will carry on his family legacy – Cordero, Tobar, or maybe both of them together, he said. But he plans to go on working as long as his father did.

Not all of Cortés’ work is for commissions. He also donates some pieces. For example, when he did the big Grotto project on the River Walk, he volunteered to build a palapa and two benches across the river at no additional cost.

“It’s the tradition of the pilon,” he said. “I want to continue to give back.” One personal project dear to his heart is restoring a large bench that incorporates branches and a tree stump that his father made in 1927.

“After I restore it and create a roof over it to protect it, I’d like to give it to the city in 2024, on the 100th anniversary of the year Dionicio Rodriguez and my father came to San Antonio,” he said. “My son said, ‘Dad, you’ve given enough away.’ But I told him ‘I’m going to give it in honor of your grandfather.’”

The biggest challenge on Cortés’ list right now is a public project in Laredo – the largest treehouse he has ever made. It has been on hold for a couple of months as he assembled a larger crew, but he plans to get back to work on it soon.

Does working on a large-scale project in cement ever make Cortés nervous?

“When I started on the Witte treehouse in ’97, it was the week my dad passed away,” he said. “I had this panic attack for a split second. I thought, ‘I don’t have that person I can go to with questions. I’ve got to do this on my own.’ But that’s how you learn. With the grotto I had that for about 30 seconds when I got started, and I thought if I failed, I was going to fail pretty big.” But then he got back to work.

As much as he has accomplished, Cortés downplays his talent.

“It’s not about me. It’s never been about me. I don’t want it to be about me,” he said.

“My wife Hope is tired of me always praising my dad, but that’s the person I look up to. He and my great-uncle are my heroes. When people say they love my work I appreciate it, but I just don’t see myself that way,” he said. Still, a spontaneous moment touches his heart.

“I remember one day I was at the Grotto on the River Walk, sitting on the bench in the center of it with the openings that let in light above me, to check out how it looked,” he said. “I saw this young mother with a child walking on the opposite bank. I could see the two benches that I did there across the river. The mother was walking ahead and her little boy came running up and I thought he was going for his mother to hug her. But he went and hugged the bench – he grabbed it and lay down on it and was touching it.

“That’s what it’s about. That’s why you do it,” he said.

###

great artist! thanks for this, Jasmina!

Such a beautiful part of San Antonio. Thanks for keeping it alive Carlos! And thank you Arts Alive San Antonio for sharing it.

Great story, Susan! Good to see your byline.