SAMA’s New Exhibit Focuses on an Enigmatic Woman

By JASMINA WELLINGHOFF, Editor

More than five centuries ago, a girl was born on the Yucatan peninsula in the Aztec Empire and she was named Malinalli. Today, so many years and centuries later, she is still an object of fascination and interpretation, both in Mexico and in Mexican-American communities in the U.S. So much so, in fact, that at least two museums have decided to tell her story in the way that art museums do – through art.

One of those is the San Antonio Museum of Art, which just opened Traitor, Survivor, Icon: The Legacy of La Malinche, a beautiful exhibit that examines the historical and cultural legacy of that girl from the Yucatan, who became known as La Malinche.

How she became La Malinche is a remarkable story of survival. Sold into slavery at a very young age, apparently by her own mother, she was living among the Maya people, when she was included in a group of twenty indigenous women given to Spanish conquistador, Hernan Cortes, as a gift from the Maya who wanted to avoid further bloodshed, after suffering huge losses at the hands of the Spaniards.

The girl – Malinalli/ Malintzen had a knack for languages and quickly learned Spanish in addition to her native Nahuatl and the Maya language she had already mastered. When Cortes realized she could be useful in negotiations with the natives, he made her his interpreter and eventually his mistress and mother of his first-born son, Martin. Though she was still a slave, she was a very useful one, credited for helping the Spanish conquer indigenous lands. Not surprisingly, the indigenous population came to see her as a traitor to her own people, dubbing her La Malinche, the epithet that stuck for centuries. In recent times however, Hispanic writers and artists on both sides of the U.S.-Mexico border – mainly women – have been reconceptualizing La Malinche, seeing themselves as her “daughters” – strong resilient women – who like her – forge new life paths for themselves.

The exhibit, which originated at the Denver Art Museum, is divided into several parts, reflecting the different roles La Malinche has played historically and culturally.

Upon entering the exhibit spaces, you’ll first encounter La Malinche as the gifted interpreter that she was. On a wall panel you’ll read among others things what Cortes himself said about her. He described her as “la lengua que yo tengo,” which translates to “the tongue I own.”

In that space you’ll also see some old drawings showing Malinche translating during a meeting of Moctezuma and Cortes, and the presentation of gifts to Cortes. Also in that room, you can watch a video of Jesusa Rodriguez performing a monologue, “The Conquest According to La Malinche.” We had no patience to listen but the actress looked very animated, apparently turning her account into political satire.

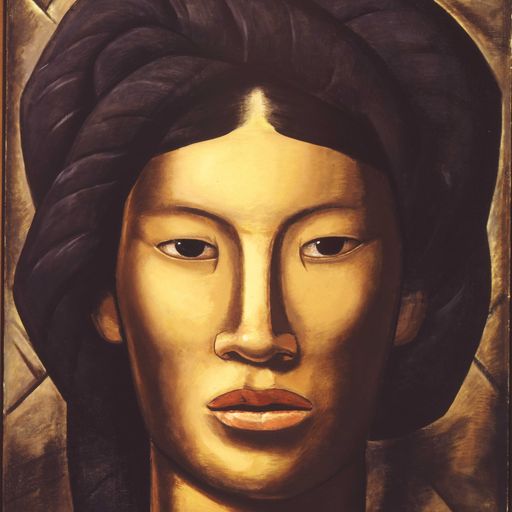

From there on, the exhibit focuses on how Malinche was interpreted by artists through time, though quite a few pieces are from the 20th century. Labeled La Indigena (The Indigenous Woman); La Madre de Mestizaje (The Mother of a Mixed Race) and La Traidora (The Traitor), these spaces feature a range of themes, formats and even media. Though most are paintings, there are two small sculptures as well, including the graceful, beautifully executed rendition in bronze by Emanuel Martinez, from 1987. Nearby is the 2018 painting showing a young La Malinche with braided hair in a central medallion, looking uncertain and anxious. On the side wall is a glamorized and romanticized image of Malinche and Cortes on a white horse by Jesus Helguera, from 1941. Images like that started appearing on Mexican calendars in the 19th century.

Following the Mexican revolution (1910-20), while Mexicans were seeking to forge a new national identity, the idea of a new mixed race became popular, a new race that mixed Spanish and indigenous ancestry. That’s how La Malinche became Mother of the Mixed Race, even though her own son was taken to Spain by Cortes when he returned home.

The Mother of the Mixed-Race section of the current exhibit has a range of powerful images showing the protagonist with Cortes in different contexts, including a large painting, “The Couple” featuring the two in a way that reveals their relationship and status. While the male figure is in a body armor and holding a sword across his and her body, she is naked and looking worried. (Jorge Gonzalez Camarena, 1964.)

Another striking work is a mural by Jose Clemente Orozco, “Cortes and Malinche,” which depicts naked seated figures, with the man restricting the woman’s arms while she is looking down at the dead indigenous person at their feet. (1926).

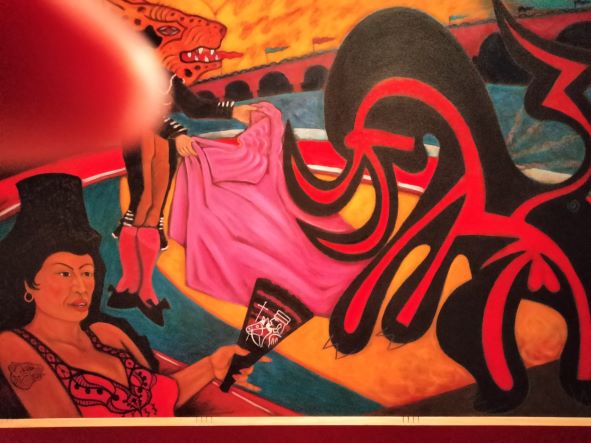

Included in the show – in the Traitor section – is also an interesting painting by Cesar Martinez, representing Malinche as Carmen (from the opera by the same name) watching a bullfighter subdue the bull, presumably helpless, or disinterested, to stop what is going on.

The last section, called Chicana – Contemporary Reclamations is pretty much what you would expect under that title. Contemporary women artists created positive images of La Malinche, to protest what they felt were misguided male interpretations of the legendary personality. Many today see her as a survivor, more than anything else.

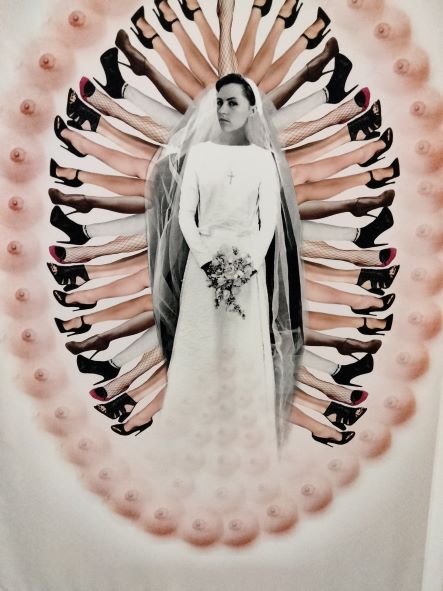

In this gallery, you’ll find “Guadinche” created by Mercedes Gertz in 2012, which features the artist herself in her mother’s wedding gown surrounded by “a fan” of women’s legs in high-heel shoes and a circle of pink round forms, resembling breasts. We believe the artist’s idea was to present herself as emerging from all those traditional symbols of femininity.

But the last image in the exhibit is a sad one. You find yourself face to face with an old woman – the artist’s grandmother, we were told during the press preview- with one of her gray braids clumsily cut off. The expression on her face is one of resignation. The artist, Gloria Ozuna Perez, named the painting “La Malinche” in 1994 when she created it, but the real Malinche never got old. She died at 29.

—————————————————————————————————-

On view Oct. 14, 2022 -January 8, 2023; San Antonio Museum of Arts; 200 W. Jones Ave.; 210-978-8140; https://www.samuseum.org; Exhibit-related special events are also scheduled, including a talk with one of the artists, Santa Barraza, on Oct. 25, and a contemporary Dance Performance by the Guadalupe Dance Company on Nov. 18 at the Guadalupe Theater. (Photos by J.W.)