American Impressionism at SAMA

By JASMINA WELLINGHOFF, Editor

While the French Impressionists are famous the world over, their American counterparts are not exactly household names even in America.

That’s where the new San Antonio Museum of Art’s exhibit, America’s Impressionism: Echoes of a Revolution can help. Consisting of more than 60 paintings, it covers a lot of territory, both artistically and geographically.

We like that subtitle “Echoes of a Revolution.” The “revolution” took place in Paris, France, when a group of younger painters who liked to paint outdoors and show landscape scenes and ordinary people in an “impressionistic style,” ruffled the feathers of the Academie des Beaux Arts in 1874. Instead of painting with realistic precision, these artists gravitated toward softer images rendered in short brush strokes and with special consideration for the effects of light as it interacts with objects and people.

Eventually, the new French ideas made it across the Atlantic Ocean, intriguing and attracting many American painters who collectively produced a novel American Impressionist movement. SAMA’s show aims to show that Americans weren’t merely copy-cats, but developed their own brand of Impressionism “shaped by American sensibilities and regional landscapes.” The exhibit originated at the Brandywine River Museum of Art in Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania, where it was curated by Amanda C. Burdan. The curator of the San Antonio version is Yinshi Lerman-Tan, who led a group of us, journalists, through the galleries last week.

Early on, she pointed out that women artists were important in the development of American Impressionism. I fact, in the small room that serves as an introduction to the exhibit, hang two paintings: Frederick Carl Frieseke’s The Bathers, and Cecilia Beaux’s “Dorothea in the Woods.” Lerman-Tan pointed out that Frieseke’s experience and work “are like a microcosm for the larger issues in the show. “He was an ex-pat from the American Mid-West, who moved to France and resided next door to Claude Monet’s estate. He’s someone who is emblematic of this transatlantic exchange, she said.” He learned impressionism in France but then “applied it to American geography.” The Bathers depicts two women, one nude and ready for a swim and the other “primly dressed.” Female nudes were a big part of Frieseke’s art, something that, again, he learned in France.

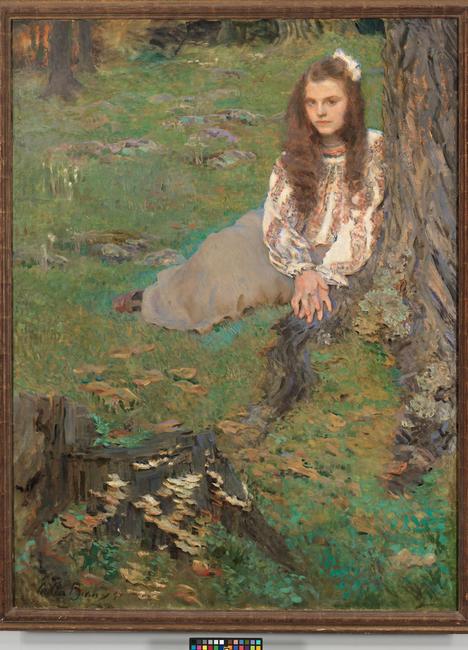

The sole other painting in that small space is Cecilia’s Beaux’s Dorothea in the Woods, showing a young girl surrounded by trees, and introducing visitors to women artists of that time. Other female Impressionists in the exhibit are Emma Richardson Cherry, Jane Peterson, Lilla Cabot Perry, Mary Cassatt, Mary Brady, Helen Turner and Elizabeth Nourse.

Like Frieseke, other Americans traveled to France – and gravitated toward one of the masters of the style, Claude Monet – resulting in a number of paintings featuring French landscapes around Giverny where Monet lived. Two examples in the exhibit are Willard Metcalf’s famous Poppy Field, from 1886, and Lilla Cabot Perry’s Old Farm, Giverny, from 1900. And there are quite a few others. Eventually, the Americans started depicting their own environments, ranging from the East Coast and Pennsylvania, all the way to California.

As you move through the galleries, you’ll encounter, William Langston Lathrop’s The Delaware Valley, John Henry Twachtman’s Connecticut landscapes, and Childe Hassam’s charming New England Country Fair. There’s even a less bucolic work, Alden Wier’ The Factory Village, featuring billowing smoke from a tall factory chimney. One of the most beautiful canvases in that section is Theodore Wendel’s, The Butterfly Catchers, an image of girls catching butterflies in a wide-open, tranquil impressionistic landscape. You may wish you were there with them.

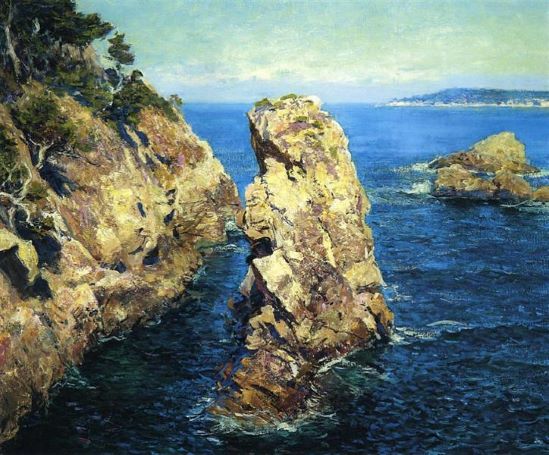

Tranquil scenes and gorgeous landscapes are still there in the works of Southwest and Texas artists – including Onderdonk’s famous expanses of bluebonnets – but new themes appear, as well, such as cattle drives, as in Driving the Herd by Frank Reaugh. It’s like a scene from old Westerns. By the time the American Impressionism makes it to California, it becomes bolder and brighter, at least as seen in this show. In Guy Rose’s Point Lobos, for instance, the deep blue ocean asserts itself in a less tranquil fashion, and Childe Hassam’s depiction of the same geographical spot, though beautiful, is not exactly a landscape to relax in.

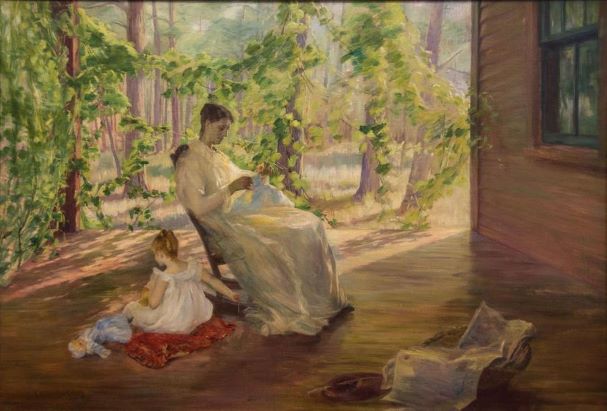

Also part of the show, is a small room dominated by smaller-scale paintings of motherhood and “the private life of women,” by Mary Cassatt, Helen Turner, and Elizabeth Nourse, the latter being the rare female artist of that time to actually make a living with her art.

Asked about the main difference between French and American Impressionism, beyond the obvious geographical differences, Lerman-Tan said: “The French Impressionism is grittier, more often dealing with social ills, while the American Impressionists conveyed a more fairy-tale, sentimentalized vision.”

——————————————————————————————————————————

San Antonio Museum of Art, 200 W. Jones Ave.; 210-978-8140; www.samuseum.org; Exhibit on view through Sept. 5, 2021; $10-$20